Two nights after Chico and I had the discussion about fluxion molecules and the urinary markings of Warrgs (and Woggs and dogs!), something happened that terrified me to the bone….an event that no one would ever want to go through. I’m fearful even as I write this. My sense of good, evil, and the dangers of the night will never be the same.

Two nights after Chico and I had the discussion about fluxion molecules and the urinary markings of Warrgs (and Woggs and dogs!), something happened that terrified me to the bone….an event that no one would ever want to go through. I’m fearful even as I write this. My sense of good, evil, and the dangers of the night will never be the same.

I hadn’t realized at first that Chico’s statements and insights were derived from his extraordinary and intuitively clear sense of the pathways of future reality. Over time, I came to understand the depth and clarity of his perceptions of future events. Chico rarely spoke more – or less! – than was needed. He seemed to expect me to be like one of his millennial compatriots: steeped in millions of years of experience and wisdom, and cognizant of the rich multivariate pathways of probability inherent in every second of time. It was both flattering and stretching: I was forced to think, imagine and project far outside the realms of comfortable future-think to which I had been accustomed, and learn the dimensions and boundaries of the present evaporating towards the instant future.

In fact, it is possible – even without a million-year background so common amongst the Woggs – to perceive the possible, likely, and even definitive pathways of the future. I suspect that they can be pushed, altered, and influenced by forces that change the nature and direction of potential pathways – but… more about that in another story.

Under Chico’s guidance, I found that I could reach outside the present instance, the current instantaneous moment of the “five fluxional pathways” (as the Woggs call them – the “snapshot” realm of possibilities ranging from probable to likely to conceivable to unlikely to nearly impossible, replete with hundreds of variable hues and nuances, but generally perceptible as broad roadways of future threaded events), and start to grasp what might be, might happen, might appear in the upcoming seconds, minutes, hours of life.

Since this applies to the life of sentient beings as well as certain objects we don’t normally think of as being “persons” or sensible elements – a rock, for example, or a tree or a mountain or geographic feature – it is possible to read the five fluxional pathways in their entirety, in a kind of zeitgeist of the moment, and interpolate a momentary intuitive perception into an upcoming event. For example, you can, if you are trained for it, know when and how there will be an automobile crash, and avoid it. You can know when a tree might fall in the forest; a cloud might dispense rain; an avalanche might begin; and a gun might be fired. Humans have tried for centuries to understand how to read these possibilities. Methods and books like the I-Ching attempt to show us how to take a “sampling of current reality to predict the future.” I cannot say if they work or not, but I suspect they might well work. The I-Ching is considered to be the oldest of all classic Chinese texts, used for over 2,500 years for grasping the present and predicting the future – as it were, taking the temperature of the instantaneous moment to divine an immediate future. Nothing lasts for 2,500 years without having a great deal of value, and the I-Ching, or “Classic Book of Changes,” is a work of inestimable insight.

Chico explained to me that every atom in the universe, and every non-atomic particle, has a perceptible pathway into the future.

I realized that when Chico would sit or stand very, very still, and barely breathe, that he was analyzing the future, and reading the five fluxional pathways. After a while, I learned to ask him, “What’s going to happen? What did you see?” Sometimes he would answer clearly, and sometimes cryptically, but there was always an answer. The clear answers were often reassuring. He provided the cryptic responses to get me to think and consider, reconsider, what I might’ve been thinking. He wanted to teach me how to read the future as he did. Chico’s sense of my perceptions was like those of an expert ancient violinist instructing students in a master class: focusing on the most important elements while suggesting an endless wealth of refinements, all in a few insightfully powerful words and gestures.

“Every particle – whether it’s a fermion or a boson,” explained Chico to me one day, “has some sort of spin, or angular momentum, and another type of spin you humans call orbital momentum. It’s what you’d really call matter – if used with words like “quark” or “lepton.” Bosons, fermions, and their internal particles – and there are a lot more of them than most physicists on your planet know about today – have specific activities which can be felt, can be read – and they have a recorded history that they are playing out in their dancing and jiggling about. In short, they speak, and their speech is extremely complex, and very compact. They speak of what they have experienced. The compilation of all of their experiences can tell you a great deal about the events of the past, and help you sense the future.”

“What?” I said in astonishment. “You mean that elementary particles are … are… telling stories about their lives?”

Chico yawned. “Yes, yes,” he said. “Sort of. In general, the particles that make up reality and matter, as you call it here on earth, express a kind of statistical reality which your scientists have called spin-statistics theory, a branch of special relativity. You can feel what they are saying, in a way…and use it to determine both the past and its projection into the future. I’m not saying that you can see them…these things are way too tiny, but you can really feel them, since they have a force that takes place in real time and real space.”

“Wow,” I gasped. “You’re using the stories told by subatomic particles to predict the future of reality pathways?”

“Yes, that’s a good way to put it,” said Chico. “The future is almost always a project of some elements of the past, and usually the most forceful past elements live on into the future in some way. But sometimes there are discontinuities, and…those can be dangerous. We can feel them when they are about to happen, since we’ve been doing this for many many centuries, many millennia. It isn’t…easy. We can feel a disturbance in the direction of the future as a potential chaotic event.”

“Is a chaotic event something bad?”

“Well,” mused Chico, “chaos isn’t usually a good thing, although the changes it brings about can be absorbed and sometimes frame new powerful, creative paths. Sometimes they are evil, and sometimes they are good. It depends upon what forces cause them.”

“So, if the Warrgs cause them, they could be evil?” I asked

“Yes, that’s so. More than likely, in fact. It’s something we try to be aware of all the time, because it holds many dangers for those whom we love.” He smiled. “Like you and your wonderful friends.”

Then he unexpectedly jumped up and licked my face, twice.

“Was that a chaotic event?” I smiled.

“No, not really. You could’ve guessed that it was coming,” grinned Chico. “From a fermion-boson standpoint, it was logical and predictable.”

There is a cute, an adorable and affectionate side to Chico that’s truly marvelous.

One evening, fairly late (I think it was approaching midnight), I decided to take Licker for a short but brisk walk. That afternoon, he hadn’t wanted to come with Chico and me on the usual bicycle-run around the neighborhood, and I was worried about his weight. Licker is almost always hungry, and – as my Jewish grandmother used to say, “He’s a nosher.” That means he likes to nibble on stuff in-between meals, and it doesn’t do his girth any good. Given how big he is (about 175 lbs.), it’s hard to tell if he’s big and strong, or just…. Big. Maybe too big. He isn’t exactly a speedy guy, unless he’s in the mood. Then he can run like the wind, really…. like a horse at full gallop. More of that later.

“Come on, Licky,” I said. “Let’s run off some of those milk-bone biscuits and rice-n-cheese snacks.” Licker looked up at me mournfully, put his head back down on the bed, and pretended to close his eyes. I got the leash and stood in front of him. He blinked. Then I said, “Hey, Licky, let’s go for a walk!” That got his attention. His ears went up like sea-gull wings, opening his aural canal for more details. “Gimme your nose,” I said. It was the classic requirement, and he always put his nose up to accept the necklace. It was, is, very cute. Then he jumped off the bed with uncharacteristic sprightliness and sauntered over to the door with me. Chico was in the yard, heard us at the door rattling the collars (I have a martingale collar for Licker, and the chain is a dead giveaway to Chico, whose hearing is more acute than a seismograph) and came bounding up. “Am I coming?” he said, nearly breathless from the sprint. “I haven’t taken Licky at all today… maybe we’ll just go on our own?” I asked. “OK, “he chortled. “I’ve got some transmissions to do for the Elders on Narsica, so I’ll focus on that. I’ll be in the yard. Howling at the moon,“ he chuckled. There wasn’t much of a moon.

I was, and continue to be, endlessly amazed at the cheerful goodwill that exudes every minute from Chico. I’ve never met anyone…. man, dog, child, saint…like him in this way. It’s more than lovable. It’s overpoweringly heart-bursting.

So, Licker and I went out the door. I pulled it shut behind me, and pressed the key-pad button to lock it. “Windy,” I thought. “Let’s not just close it somewhat. Needs locking.” I had a premonition of unsafe moments.

It’s hard to describe the tenor of that evening. Everything I remember is so conditioned by the events that occurred….so my historical perspectives are fraught with pregnant perceptions. There was a thin moon, perhaps about a quarter-moon, and it was low on the horizon. The moon’s glow through the eastern trees provided a bit of light, but tremulous and uncertain. As the rather winter-naked trees nocturned in the wind, the pale, almost sickly light grazing through them was weak. The shadows were deep, and even fearsome, cold, uninviting. I stopped to let Licky do some sniffing.

He spent more time sniffing than I would’ve considered ordinary. Yet, sometimes Licky was more than thorough…. nearly compulsively detailed. I knew he perceived something different, something he hadn’t truly encountered before. He snorted after several minutes’ sniffing, as if to say, “I don’t like that odor. I don’t want it around.” In fact, he hunched down and peed on it. A true mark of disdain, surely.

We turned to the west, with the moon behind us; the dim light and fragrance of the moon filtered by and through the spring wind-swept nearly naked trees. No sound, but the occasional groans of a yawning tree, its last few leaves of summer cracking like dried carcasses of now-silent crickets. We walked around the back of the Coral Gables library, a lovely, limestone-coated structure of yore, silently pregnant with the voices of thousands of wise books, noble in its oak-beamed linseed-redolent exposed roofing and country Mexican tile floor. We turned from a dimly lit façade onto an unlit street, heading southwards towards home. The winds nearly stopped, and the cricket-less silence was anything but reassuring.

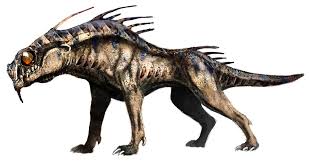

Licky stopped dead, and I felt it in his leash. He crouched down several inches, nose in the air, high. He growled low and throaty. I couldn’t remember ever seeing him posture in such a threatening, yet defensive fashion, and his vocalization was unknown to me. I glanced up, and saw what looked like the shadow of a huge tree over-arching the pathway next to the library’s butterfly garden, and realized there was no moon high enough to cast a shadow. It was something, something which hadn’t been there a minute earlier. I glanced back down at Licky, and the hair on his back was like a porcupine’s quills, bristling with fury as his throaty growl became a warrior’s scream. I’d never, ever heard Licker scream like that. I knew there was something to be afraid of, something terrifying, terrible, unknown and of extreme danger. Dumbstruck, his leash fell from my hand, and as if in a slow-motion echo chamber, I heard the dry crisp wrinkling of crushed leaves under it. I stood frozen, transfixed and terrified.

But not so Licker. In an instant’s crouch, he sprang forward with the power and speed of a charging bull, intent to pin the matador into his waving cloak in the twinkling of a terrible and furious eye. He seemed to grow larger as he bounded forwards, doubling his speed with every leap, until he literally flew off the ground at the shadow-like being which blocked our path. The creature snarled and hissed like a striking snake, and I saw the glint of steel-blue teeth and glowing enormous cat-like eyes. Licky hit the thing, full-on, at its shoulder. The shadow swirled, screamed like a wounded loon, and Licker tumbled towards the garden, rolling and rolling. “No, no, no!” I screamed, “no, o my God, Licky Licky!” Unmindful of danger, I ran towards the beast, planning to swerve around it and go to Licker. My love for my friend was a million times greater than any fear I might ever conjure. In fact, my fear didn’t exist.

And then something totally unexpected happened, completely, totally unanticipated. Over my right shoulder another creature, with a jet-like whoosh, launched itself into the air…a creature nearly as huge as the Warrg that blocked my path, glowing golden brown and white with piercing, laser-like blue and brown shafts of light streaming from its eye-sockets. It was Chico! But a huge, angry, warlike Chico, with enormous curved white-hot steel shafts bristling from his front paws, and a toothed, muscular mouth as large and flashing as a great white shark. In a fraction of a second, he attacked the shadow Warrg, and there was an earth-shattering crash as his paws slashed into the huge shadow-like being, and his mouth turned and grasped like a death-vise the space just below the shadow’s head. There was a burst of blue light, a crack like an ice-sheaf shearing….and then silence. The shadow disappeared. Chico was on the ground, head down, paws withdrawn, as if exhausted. And indeed, he was. I ran up to him, and he looked up at me. “Pick up Licky” he gasped. I ran to Licker and turned him over, my heart pounding, almost expecting him to be dead. He looked up at me, raised his head to lick my face, shook himself, and got up. A long, ugly dry scar – no blood – protruded from his left side, but he seemed to be fine. He shook himself again, from head to tail, squealed and yawned, and trotted over to Chico, now his normal size, and ordinary appearance.

“Let’s go home,” said Chico. “Enough excitement for one night’s battle.” He paused. “I’m afraid there are going to be more of these. I must accelerate your training… the training of all of you, without exception. Good sense requires it. You must learn to teleport, and you will need to learn defensive battle techniques.”

“I’ll learn anything needed,” I said. “I’m just glad you showed up.”

“Well, honestly, I sensed that it was coming, so I wasn’t unprepared. Over the last few days there has been a lot of recent Warrg activity around here…. I think they were actually planning to attack me, and my compatriots on Narsica warned me that something like this might happen. I was worried when you left. But I have faith in you, and in Licker, especially. He’s a remarkable fellow.”

“Yes, yes, you’re right,” I said, and stopped to get down on one knee and hug Licky’s huge head. “You saved me, Licky…just like Chico predicted.” Licky just smiled and yawned, as if to say, “Yeah, so what? Let’s go home to bed.”